使用者:Flsxx/測試

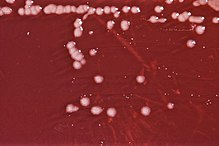

假單胞菌屬(Pseudomonas)是假單胞菌科(Pseudomonadaceae)的一屬,為一種革蘭氏陰性菌。假單胞菌屬廣泛分布於土壤和水體中,在人體中亦有分布,多為化能有機營養型,某些種為兼性化能無機營養型,專性氧化(呼吸)代謝,所有種都以氧為最終電子受體,一些能以硝酸鹽呼吸。細胞形態典型為極生鞭毛桿菌,體多呈現直或微彎的杆狀,無菌柄及鞘,不產芽孢,許多種能夠積累聚-β-羥基丁酸鹽,作為儲藏物質。大多數種能以單級毛或多級毛運動,進行呼吸性代謝,最終電子受體為氧,銅綠假單胞菌和個別情況下以硝酸鹽為電子受體,進行厭氧呼吸,進行反硝化作用。一些種對植物及人畜具有致病性,如銅綠假單胞菌(P. aeruginosa)、鼻疽假單胞菌(P. mallei)和青枯病假單胞菌(P. solanacearum)等。直徑約0.5至1微米,長約1至4微米。該屬基因組DNA的GC比範圍為58-69%。[1]

該屬的模式種為銅綠假單胞菌。目前臨床上越來越多地將銅綠假單胞菌視作一種條件致病菌,幾種不同的流行病學研究表明,其臨床分離菌株的抗生素耐藥性呈現上升趨勢。[2]

該屬的種在代謝上表現出極大的多樣性,因此能在多種生境下生長。由於該屬的細菌易於進行體外培養,並且人們已經對該屬下越來越多個種的基因組加以研究,假單胞菌屬已經成為重要的科研對象,主要的有人體條件致病菌銅綠假單胞菌、植物致病菌丁香假單胞菌、土壤細菌惡臭假單胞菌和植物促生菌螢光假單胞菌等。[3]

由於假單胞菌在水體及植物種子(如雙子葉植物)上廣泛分布,在微生物學領域已經早有研究。Walter Migula在1894年和1900年給「假單胞菌」這一屬名的定義相當模糊,是指一種革蘭氏陰性、棒狀、極生鞭毛的細菌,一些種能產生孢子。[4][5]但關於孢子的描述事後證明是錯誤的,這是一些儲藏物質的折光性造成的誤判。[6] Despite the vague description, the type species, Pseudomonas pyocyanea (basonym of Pseudomonas aeruginosa), proved the best descriptor.[6]

分類歷史

[編輯]最初對假單胞菌進行分類是在19世紀末Walter Migula最早鑑別出該屬的時候,至於這一名稱的構詞法,在當時並無明確說法,最早提到則在伯傑系統細菌學手冊的第7版上,稱是希臘語 ψευδες(pseudes,「假的」)和 μονάς / μονάδα(-monas,「單個」);但也可能Migula的本意就是指「假的」滴蟲(Monas,一種鞭毛蟲類原生生物)。後來,monad一詞在早期微生物學史上用於表示單細胞生物。[6]不久以後,許多與Migula最初的模糊描述有或多或少匹配的物種被從各種生境中分離出來,在當時其中許多被分類到這個屬。但是,後來人們用更新的分類學原則,並採用諸如保守生物大分子研究等更多手段,將其中一些物種重新分類歸於其他屬。[7]

最近,16S rRNA的序列分析使得許多細菌的分類再次受到挑戰。[8]結果,金色單胞菌屬(Chryseomonas)和黃色單胞菌屬(Flavimonas)的種被併入假單胞菌屬。[9]一些原屬於假單胞菌屬的種被劃分到伯克氏菌屬(Burkholderia)及雷爾氏菌屬(Ralstonia)。[10][11]

2000年,人們得到了第一個假單胞菌屬菌株的全基因組序列,近年來更多菌株的序列也測序完成,包括銅綠假單胞菌PAO1(2000年)、惡臭假單胞菌KT2440(2002年)、P. protegens Pf-5(2005年)、綠針假單胞菌GP72(2012年)等。[7][12]

2008年在《科學美國人》(Scientific American)上發表的一篇文章表明,假單胞菌可能是雲當中冰晶最常見的成核中心,可能說明假單胞菌對地球上雨和雪的形成起到了有極為重要的作用。[13]

特徵

[編輯]假單胞菌屬的種符合以下的定義性特徵:[14]

- 棒狀;

- 革蘭氏陰性;

- 單極或多極鞭毛,可運動;

- 好氧;

- 不產芽孢;

- 過氧化氫酶檢測陽性;

- 氧化酶檢測陽性。

也有其他一些僅能夠判定可能屬於假單胞菌屬的特徵(有例外),包括在環境鐵含量不足的情況下分泌綠膿菌螢光素(pyoverdine,一種有螢光的黃綠色鐵載體),[15]一些特定的假單胞菌還能產生另一些鐵載體,如銅綠假單胞菌代謝產生綠膿菌素,[16],或螢光假單胞菌代謝產生thioquinolobactin。[17]

生物膜的形成

[編輯]All species and strains of Pseudomonas are Gram-negative rods, and have historically been classified as strict aerobes. Exceptions to this classification have recently been discovered in Pseudomonas biofilms.[18] A significant number of cells can produce exopolysaccharides which are associated with biofilm formation. Secretion of exopolysaccharide such as alginate, makes it difficult for pseudomonads to be phagocytosed by mammalian white blood cells.[19] Exopolysaccharide production also contributes to surface-colonising biofilms which are difficult to remove from food preparation surfaces. Growth of pseudomonads on spoiling foods can generate a "fruity" odor.

Pseudomonas have the ability to metabolize a variety of nutrients. Combined with the ability to form biofilms, they are thus able to survive in a variety of unexpected places. For example, they have been found in areas where pharmaceuticals are prepared. A simple carbon source, such as soap residue or cap liner-adhesives is a suitable place for them to thrive. Other unlikely places where they have been found include antiseptics, such as quaternary ammonium compounds, and bottled mineral water.

Antibiotic resistance

[編輯]Being Gram-negative bacteria, most Pseudomonas spp. are naturally resistant to penicillin and the majority of related beta-lactam antibiotics, but a number are sensitive to piperacillin, imipenem, ticarcillin, or ciprofloxacin.[19] Aminoglycosides such as tobramycin, gentamicin, and amikacin are other choices for therapy.

This ability to thrive in harsh conditions is a result of their hardy cell wall that contains porins. Their resistance to most antibiotics is attributed to efflux pumps, which pump out some antibiotics before the antibiotics are able to act.

Pseudomonas aeruginosa is a highly relevant opportunistic human pathogen. One of the most worrying characteristics of P. aeruginosa is its low antibiotic susceptibility. This low susceptibility is attributable to a concerted action of multidrug efflux pumps with chromosomally encoded antibiotic resistance genes (e.g. mexAB-oprM, mexXY, etc.,[20]) and the low permeability of the bacterial cellular envelopes. Besides intrinsic resistance, P. aeruginosa easily develops acquired resistance either by mutation in chromosomally encoded genes, or by the horizontal gene transfer of antibiotic resistance determinants. Development of multidrug resistance by P. aeruginosa isolates requires several different genetic events that include acquisition of different mutations and/or horizontal transfer of antibiotic resistance genes. Hypermutation favours the selection of mutation-driven antibiotic resistance in P. aeruginosa strains producing chronic infections, whereas the clustering of several different antibiotic resistance genes in integrons favours the concerted acquisition of antibiotic resistance determinants. Some recent studies have shown phenotypic resistance associated to biofilm formation or to the emergence of small-colony-variants may be important in the response of P. aeruginosa populations to antibiotic treatment.[7]

Taxonomy

[編輯]The studies on the taxonomy of this complicated genus groped their way in the dark while following the classical procedures developed for the description and identification of the organisms involved in sanitary bacteriology during the first decades of the 20th century. This situation sharply changed with the proposal to introduce as the central criterion the similarities in the composition and sequences of macromolecular components of the ribosomal RNA. The new methodology clearly showed the genus Pseudomonas, as classically defined, consisted in fact of a conglomerate of genera that could clearly be separated into five so-called rRNA homology groups. Moreover, the taxonomic studies suggested an approach that might prove useful in taxonomic studies of all other prokaryotic groups. A few decades after the proposal of the new genus Pseudomonas by Migula in 1894, the accumulation of species names assigned to the genus reached alarming proportions. At present, the number of species in the current list has contracted more than 90%. In fact, this approximated reduction may be even more dramatic if one considers the present list contains many new names, i.e., relatively few names of the original list survived in the process. The new methodology and the inclusion of approaches based on the studies of conservative macromolecules other than rRNA components, constitutes an effective prescription that helped to reduce Pseudomonas nomenclatural hypertrophy to a manageable size.[7]

Pathogenicity

[編輯]Animal pathogens

[編輯]Infectious species include P. aeruginosa, P. oryzihabitans, and P. plecoglossicida. P. aeruginosa flourishes in hospital environments, and is a particular problem in this environment since it is the second most common infection in hospitalized patients (nosocomial infections). This pathogenesis may in part be due to the proteins secreted by P. aeruginosa. The bacterium possesses a wide range of secretion systems, which export numerous proteins relevant to the pathogenesis of clinical strains.[21]

Plant pathogens

[編輯]P. syringae is a prolific plant pathogen. It exists as over 50 different pathovars, many of which demonstrate a high degree of host plant specificity. There are numerous other Pseudomonas species that can act as plant pathogens, notably all of the other members of the P. syringae subgroup, but P. syringae is the most widespread and best studied.

Although not strictly a plant pathogen, P. tolaasii can be a major agricultural problem, as it can cause bacterial blotch of cultivated mushrooms.[22] Similarly, P. agarici can cause drippy gill in cultivated mushrooms.[23]

Use as biocontrol agents

[編輯]Since the mid-1980s, certain members of the Pseudomonas genus have been applied to cereal seeds or applied directly to soils as a way of preventing the growth or establishment of crop pathogens. This practice is generically referred to as biocontrol. The biocontrol properties of P. fluorescens and P. protegens strains (CHA0 or Pf-5 for example) are currently best understood, although it is not clear exactly how the plant growth-promoting properties of P. fluorescens are achieved. Theories include: that the bacteria might induce systemic resistance in the host plant, so it can better resist attack by a true pathogen; the bacteria might out compete other (pathogenic) soil microbes, e.g. by siderophores giving a competitive advantage at scavenging for iron; the bacteria might produce compounds antagonistic to other soil microbes, such as phenazine-type antibiotics or hydrogen cyanide. There is experimental evidence to support all of these theories.[24]

Other notable Pseudomonas species with biocontrol properties include P. chlororaphis, which produces a phenazine-type antibiotic active agent against certain fungal plant pathogens,[25] and the closely related species P. aurantiaca which produces di-2,4-diacetylfluoroglucylmethane, a compound antibiotically active against Gram-positive organisms.[26]

Use as bioremediation agents

[編輯]Some members of the genus Pseudomonas are able to metabolise chemical pollutants in the environment, and as a result can be used for bioremediation. Notable species demonstrated as suitable for use as bioremediation agents include:

- P. alcaligenes, which can degrade polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons.[27]

- P. mendocina, which is able to degrade toluene.[28]

- P. pseudoalcaligenes is able to use cyanide as a nitrogen source.[29]

- P. resinovorans can degrade carbazole.[30]

- P. veronii has been shown to degrade a variety of simple aromatic organic compounds.[31][32]

- P. putida has the ability to degrade organic solvents such as toluene.[33] At least one strain of this bacterium is able to convert morphine in aqueous solution into the stronger and somewhat expensive to manufacture drug hydromorphone (Dilaudid).

- Strain KC of P. stutzeri is able to degrade carbon tetrachloride.[34]

Food spoilage agents

[編輯]As a result of their metabolic diversity, ability to grow at low temperatures and ubiquitous nature, many Pseudomonas spp. can cause food spoilage. Notable examples include dairy spoilage by P. fragi,[35] mustiness in eggs caused by P. taetrolens and P. mudicolens,[36] and P. lundensis, which causes spoilage of milk, cheese, meat, and fish.[37]

Species previously classified in the genus

[編輯]Recently, 16S rRNA sequence analysis redefined the taxonomy of many bacterial species previously classified as being in the Pseudomonas genus.[8] Species which moved from the Pseudomonas genus are listed below; clicking on a species will show its new classification. Note that the term 'pseudomonad' does not apply strictly to just the Pseudomonas genus, and can be used to also include previous members such as the genera Burkholderia and Ralstonia.

α proteobacteria: P. abikonensis, P. aminovorans, P. azotocolligans, P. carboxydohydrogena, P. carboxidovorans, P. compransoris, P. diminuta, P. echinoides, P. extorquens, P. lindneri, P. mesophilica, P. paucimobilis, P. radiora, P. rhodos, P. riboflavina, P. rosea, P. vesicularis.

β proteobacteria: P. acidovorans, P. alliicola, P. antimicrobica, P. avenae, P. butanovorae, P. caryophylli, P. cattleyae, P. cepacia, P. cocovenenans, P. delafieldii, P. facilis, P. flava, P. gladioli, P. glathei, P. glumae, P. graminis, P. huttiensis, P. indigofera, P. lanceolata, P. lemoignei, P. mallei, P. mephitica, P. mixta, P. palleronii, P. phenazinium, P. pickettii, P. plantarii, P. pseudoflava, P. pseudomallei, P. pyrrocinia, P. rubrilineans, P. rubrisubalbicans, P. saccharophila, P. solanacearum, P. spinosa, P. syzygii, P. taeniospiralis, P. terrigena, P. testosteroni.

γ-β proteobacteria: P. beteli, P. boreopolis, P. cissicola, P. geniculata, P. hibiscicola, P. maltophilia, P. pictorum.

γ proteobacteria: P. beijerinckii, P. diminuta, P. doudoroffii, P. elongata, P. flectens, P. halodurans, P. halophila, P. iners, P. marina, P. nautica, P. nigrifaciens, P. pavonacea, P. piscicida, P. stanieri.

δ proteobacteria: P. formicans.

Bacteriophage

[編輯]There are a number of bacteriophage that infect Pseudomonas, e.g.

- Pseudomonas phage Φ6

- Pseudomonas aeruginosa phage EL [38]

- Pseudomonas aeruginosa phage ΦKMV [39]

- Pseudomonas aeruginosa phage LKD16 [40]

- Pseudomonas aeruginosa phage LKA1 [40]

- Pseudomonas aeruginosa phage LUZ19

- Pseudomonas aeruginosa phage ΦKZ [38]

See also

[編輯]- culture collection for a list of culture collections

Footnotes

[編輯]<references>標籤中name屬性為「name」的參考文獻沒有在文中使用References

[編輯]- ^ 周德慶, 徐士菊. 微生物學辭典. 天津: 天津科學技術出版社, 2005.

- ^ Van Eldere J. Multicentre surveillance of Pseudomonas aeruginosa susceptibility patterns in nosocomial infections. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2003, 51 (2): 347–352. PMID 12562701. doi:10.1093/jac/dkg102. 已忽略未知參數

|month=(建議使用|date=) (幫助) - ^ 3.0 3.1 Madigan M; Martinko J (editors). Brock Biology of Microorganisms 11th. Prentice Hall. 2005. ISBN 0-13-144329-1. 引用錯誤:帶有name屬性「Brock」的

<ref>標籤用不同內容定義了多次 - ^ Migula, W. (1894) Über ein neues System der Bakterien. Arb Bakteriol Inst Karlsruhe 1: 235–328.

- ^ Migula, W. (1900) System der Bakterien, Vol. 2. Jena, Germany: Gustav Fischer.

- ^ 6.0 6.1 6.2 Norberto J. Palleroni. The Pseudomonas Story: Editorial. Environmental Microbiology. 2010-06-07, 12 (6): 1377–1383 [2019-06-25]. doi:10.1111/j.1462-2920.2009.02041.x (英語).

- ^ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 Cornelis P (editor). Pseudomonas: Genomics and Molecular Biology 1st. Caister Academic Press. 2008. ISBN 1-904455-19-0.

- ^ 8.0 8.1 Anzai Y, Kim H, Park, JY, Wakabayashi H. Phylogenetic affiliation of the pseudomonads based on 16S rRNA sequence. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2000, 50 (4): 1563–89. PMID 10939664. doi:10.1099/00207713-50-4-1563.

- ^ Anzai, Y; Kudo, Y; Oyaizu, H. The phylogeny of the genera Chryseomonas, Flavimonas, and Pseudomonas supports synonymy of these three genera. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1997, 47 (2): 249–251. PMID 9103607. doi:10.1099/00207713-47-2-249. 已忽略未知參數

|unused_data=(幫助) - ^ E. Yabuuchi, Y. Kosako, H. Oyaizu, I. Yano, H. Hotta, Y. Hashimoto, T. Ezaki, M. Arakawa. Proposal of Burkholderia gen. nov. and transfer of seven species of the genus Pseudomonas homology group II to the new genus, with the type species Burkholderia cepacia (Palleroni and Holmes 1981) comb. nov. Microbiology and Immunology. 1992, 36 (12): 1251–1275 [2019-06-25]. ISSN 0385-5600. PMID 1283774.

- ^ E. Yabuuchi, Y. Kosako, I. Yano, H. Hotta, Y. Nishiuchi. Transfer of two Burkholderia and an Alcaligenes species to Ralstonia gen. Nov.: Proposal of Ralstonia pickettii (Ralston, Palleroni and Doudoroff 1973) comb. Nov., Ralstonia solanacearum (Smith 1896) comb. Nov. and Ralstonia eutropha (Davis 1969) comb. Nov. Microbiology and Immunology. 1995, 39 (11): 897–904 [2019-06-25]. ISSN 0385-5600. PMID 8657018.

- ^ X. Shen, M. Chen, H. Hu, W. Wang, H. Peng, P. Xu, X. Zhang. Genome Sequence of Pseudomonas chlororaphis GP72, a Root-Colonizing Biocontrol Strain. Journal of Bacteriology. 2012-03-01, 194 (5): 1269–1270 [2019-06-25]. ISSN 0021-9193. PMC 3294805

. PMID 22328763. doi:10.1128/JB.06713-11 (英語).

. PMID 22328763. doi:10.1128/JB.06713-11 (英語).

- ^ Do Microbes Make Snow?

- ^ Krieg, Noel. Bergey's Manual of Systematic Bacteriology, Volume 1. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins. 1984. ISBN 0-683-04108-8.

- ^ Meyer JM; Geoffroy VA; Baida N; et al. Siderophore typing, a powerful tool for the identification of fluorescent and nonfluorescent pseudomonads. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2002, 68 (6): 2745–2753. PMC 123936

. PMID 12039729. doi:10.1128/AEM.68.6.2745-2753.2002. 已忽略未知參數

. PMID 12039729. doi:10.1128/AEM.68.6.2745-2753.2002. 已忽略未知參數|author-separator=(幫助) - ^ Lau GW, Hassett DJ, Ran H, Kong F. The role of pyocyanin in Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection. Trends in molecular medicine. 2004, 10 (12): 599–606. PMID 15567330. doi:10.1016/j.molmed.2004.10.002.

- ^ Matthijs S, Tehrani KA, Laus G, Jackson RW, Cooper RM, Cornelis P. Thioquinolobactin, a Pseudomonas siderophore with antifungal and anti-Pythium activity. Environ. Microbiol. 2007, 9 (2): 425–434. PMID 17222140. doi:10.1111/j.1462-2920.2006.01154.x.

- ^ Hassett D, Cuppoletti J, Trapnell B, Lymar S, Rowe J, Yoon S, Hilliard G, Parvatiyar K, Kamani M, Wozniak D, Hwang S, McDermott T, Ochsner U. Anaerobic metabolism and quorum sensing by Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms in chronically infected cystic fibrosis airways: rethinking antibiotic treatment strategies and drug targets. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2002, 54 (11): 1425–1443. PMID 12458153. doi:10.1016/S0169-409X(02)00152-7.

- ^ 19.0 19.1 Ryan KJ; Ray CG (editors). Sherris Medical Microbiology 4th. McGraw Hill. 2004. ISBN 0-8385-8529-9.

- ^ Poole K. Efflux-mediated multiresistance in Gram-negative bacteria. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2004, 10 (1): 12–26. PMID 14706082. doi:10.1111/j.1469-0691.2004.00763.x. 已忽略未知參數

|month=(建議使用|date=) (幫助) - ^ Hardie. The Secreted Proteins of Pseudomonas aeruginosa: Their Export Machineries, and How They Contribute to Pathogenesis. Bacterial Secreted Proteins: Secretory Mechanisms and Role in Pathogenesis. Caister Academic Press. 2009. ISBN 978-1-904455-42-4.

- ^ Brodey CL, Rainey PB, Tester M, Johnstone K. Bacterial blotch disease of the cultivated mushroom is caused by an ion channel forming lipodepsipeptide toxin. Molecular Plant–Microbe Interaction. 1991, 1 (4): 407–11. doi:10.1094/MPMI-4-407.

- ^ Young JM. Drippy gill: a bacterial disease of cultivated mushrooms caused by Pseudomonas agarici n. sp. NZ J Agric Res. 1970, 13 (4): 977–90. doi:10.1080/00288233.1970.10430530.

- ^ Haas D, Defago G. Biological control of soil-borne pathogens by fluorescent pseudomonads. Nature Reviews in Microbiology. 2005, 3 (4): 307–319. PMID 15759041. doi:10.1038/nrmicro1129.

- ^ Chin-A-Woeng TF; et al. Root colonization by phenazine-1-carboxamide-producing bacterium Pseudomonas chlororaphis PCL1391 is essential for biocontrol of tomato foot and root rot. Mol Plant Microbe Interact. 2000, 13 (12): 1340–1345. PMID 11106026. doi:10.1094/MPMI.2000.13.12.1340. 已忽略未知參數

|author-separator=(幫助) - ^ Esipov; et al. New antibiotically active fluoroglucide from Pseudomonas aurantiaca. Antibiotiki. 1975, 20 (12): 1077–81. PMID 1225181.

- ^ O'Mahony MM, Dobson AD, Barnes JD, Singleton I. The use of ozone in the remediation of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon contaminated soil. Chemosphere. 2006, 63 (2): 307–314. PMID 16153687. doi:10.1016/j.chemosphere.2005.07.018.

- ^ Yen KM; Karl MR; Blatt LM; et al. Cloning and characterization of a Pseudomonas mendocina KR1 gene cluster encoding toluene-4-monooxygenase. J. Bacteriol. 1991, 173 (17): 5315–27. PMC 208241

. PMID 1885512. 已忽略未知參數

. PMID 1885512. 已忽略未知參數|author-separator=(幫助) - ^ Huertas MJ; Luque-Almagro VM; Martínez-Luque M; et al. Cyanide metabolism of Pseudomonas pseudoalcaligenes CECT5344: role of siderophores. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2006, 34 (Pt 1): 152–5. PMID 16417508. doi:10.1042/BST0340152. 已忽略未知參數

|author-separator=(幫助) - ^ Nojiri H; Maeda K; Sekiguchi H; et al. Organization and transcriptional characterization of catechol degradation genes involved in carbazole degradation by Pseudomonas resinovorans strain CA10. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2002, 66 (4): 897–901. PMID 12036072. doi:10.1271/bbb.66.897. 已忽略未知參數

|author-separator=(幫助) - ^ Nam; et al. A novel catabolic activity of Pseudomonas veronii in biotransformation of pentachlorophenol. Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology. 2003, 62 (2–3): 284–290. PMID 12883877. doi:10.1007/s00253-003-1255-1.

- ^ Onaca; et al. Degradation of alkyl methyl ketones by Pseudomonas veronii. Journal of Bacteriology. 2007 Mar 9, 189 (10): 3759–3767. PMC 1913341

. PMID 17351032. doi:10.1128/JB.01279-06. 已忽略未知參數

. PMID 17351032. doi:10.1128/JB.01279-06. 已忽略未知參數|unused_data=(幫助); - ^ Marqués S, Ramos JL. Transcriptional control of the Pseudomonas putida TOL plasmid catabolic pathways. Mol. Microbiol. 1993, 9 (5): 923–929. PMID 7934920. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2958.1993.tb01222.x.

- ^ Sepulveda-Torres; et al. Generation and initial characterization of Pseudomonas stutzeri KC mutants with impaired ability to degrade carbon tetrachloride. Arch Microbiol. 1999, 171 (6): 424–429. PMID 10369898. doi:10.1007/s002030050729.

- ^ Pereira, JN, and Morgan, ME. Nutrition and physiology of Pseudomonas fragi. J Bacteriol. 1957 Dec, 74 (6): 710–3. PMC 289995

. PMID 13502296.

. PMID 13502296.

- ^ Levine, M, and Anderson, DQ. Two New Species of Bacteria Causing Mustiness in Eggs. J Bacteriol. 1932 Apr, 23 (4): 337–47. PMC 533329

. PMID 16559557.

. PMID 16559557.

- ^ Gennari, M, and Dragotto, F. A study of the incidence of different fluorescent Pseudomonas species and biovars in the microflora of fresh and spoiled meat and fish, raw milk, cheese, soil and water. J Appl Bacteriol. 1992 Apr, 72 (4): 281–8. PMID 1517169. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2672.1992.tb01836.x.

- ^ 38.0 38.1 Kirsten Hertveldt, Rob Lavigne, Elena Pleteneva, Natalia Sernova, Lidia Kurochkina, Roman Korchevskii, Johan Robben, Vadim Mesyanzhinov, Victor N. Krylov, Guido Volckaert. Genome comparison of Pseudomonas aeruginosa large phages. Journal of Molecular Biology. 2005-12-02, 354 (3): 536–545 [2019-06-25]. ISSN 0022-2836. PMID 16256135. doi:10.1016/j.jmb.2005.08.075.

- ^ Rob Lavigne, Jean-Paul Noben, Kirsten Hertveldt, Pieter-Jan Ceyssens, Yves Briers, Debora Dumont, Bart Roucourt, Victor N. Krylov, Vadim V. Mesyanzhinov, Johan Robben, Guido Volckaert. The structural proteome of Pseudomonas aeruginosa bacteriophage phiKMV. Microbiology (Reading, England). 2006-02, 152 (Pt 2): 529–534 [2019-06-25]. ISSN 1350-0872. PMID 16436440. doi:10.1099/mic.0.28431-0.

- ^ 40.0 40.1 Pieter-Jan Ceyssens, Rob Lavigne, Wesley Mattheus, Andrew Chibeu, Kirsten Hertveldt, Jan Mast, Johan Robben, Guido Volckaert. Genomic analysis of Pseudomonas aeruginosa phages LKD16 and LKA1: establishment of the phiKMV subgroup within the T7 supergroup. Journal of Bacteriology. 2006-10, 188 (19): 6924–6931 [2019-06-25]. ISSN 0021-9193. PMC 1595506

. PMID 16980495. doi:10.1128/JB.00831-06.

. PMID 16980495. doi:10.1128/JB.00831-06.

- ^ R. E. Buchanan. Taxonomy. Annual Review of Microbiology. 1955, 9: 1–20 [2019-06-25]. ISSN 0066-4227. PMID 13259458. doi:10.1146/annurev.mi.09.100155.000245.