树懒

| 樹懶亞目 化石时期:

| |

|---|---|

| |

| 褐喉樹懶,攝於哥斯大黎加卡維塔國家公園 | |

| 科学分类 | |

| 界: | 动物界 Animalia |

| 门: | 脊索动物门 Chordata |

| 纲: | 哺乳纲 Mammalia |

| 高目: | 大西洋獸高目 Atlantogenata |

| 总目: | 异关节总目 Xenarthra |

| 目: | 披毛目 Pilosa |

| 亚目: | 食葉亞目 Folivora Delsuc et al, 2001 |

| 科 | |

樹懶,也作樹獺[1],是哺乳綱異關節總目披毛目下樹懒亞目(学名:Folivora)物種的通稱,又稱為食葉亞目,包括有樹懶科和二趾樹懶科。其移動速度非常地慢,只有每分鐘4米(0.24km/h)的速度,在地面上是只有每分钟2米(0.12km/h)的速度。如果不慎掉到地面,容易成为其他肉食性动物的猎物,然而牠們具有游泳的能力[2]。共有兩科六種,分布於南美洲及中美洲的熱帶雨林中,雖然外觀上相似,但兩科之間的分別頗大。雖然被稱為二趾與三趾樹懶,但其實所有現存的樹懶均有3根腳趾,主要差異在於,二趾樹懶的前臂上僅有二指[3]。

樹懶的粗毛夾縫中長有與其互利共生的綠藻,提供很好的保護色,而樹懶有時也會取食身上的綠藻作為營養來源。而這些綠藻也是樹懶蛾的食物來源,有些種類的樹懶蛾甚至只能在樹懶身上發現[4]。

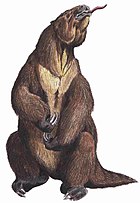

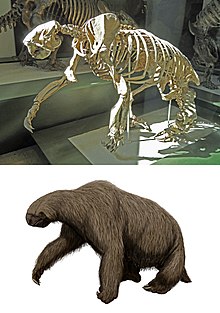

絕種的樹懶包括地懶,其中體型最大的大地懶全長可達6米(20英尺)[5][6],相當於現今的非洲象。

分類

[编辑]異關節總目是一群6千萬年前演化自南美洲的有胎盤哺乳動物[7],與其他有胎盤哺乳動物於約1億年前分家[8]。目前已知最早的異關節總目物種為樹棲的草食動物,具有粗壯的脊椎、癒合的骨盆、粗壯的牙齒以及較小的腦。異關節總目中的現存物種也包含食蟻獸和犰狳。樹懶屬於異關節總目披毛目下的樹懶亞目[9],其學名「Folivora」拉丁文意思為「食葉者」。

樹懶亞目共有8科,其中6科成員已完全滅絕[10],現存成員共兩科六種如下所示:

- 大地懶總科 Megatheroidea

- 磨齒獸總科 Mylodontoidea

演化

[编辑]三趾樹懶與二趾樹懶約於2千8百萬年前分家[10],現今兩者外型與樹棲行為類似是趨同演化後的結果[15]。有關於樹懶雙起源的假說藉由研究其內耳構造的形態學提供支持[16]。過去的異關節總目包含了更多樣化的物種,並分布於更為廣泛的區域。已滅絕的樹懶多半棲息於地面,並被稱為是地懶,體型最大的大地懶甚至可與大象相當[2]。

地懶在獨立的南美洲大陸上演化,並在之後透過牠們卓越的游泳能力於漸新世時海洋播遷至安地列斯群島,巨爪地懶科的Pliometanastes及磨齒獸科的Thinobadistes於約900萬年前抵達北美洲,遠早於巴拿馬地峽的形成。300萬年前,大地懶科與懶獸科物種於南北美洲生物大遷徙時也抵達北美洲。南美洲西岸的地懶則演化出了半水生甚至之後完全水生的海懶獸屬[17]。在中新世晚期的祕魯與智利,海懶獸屬的物種最初僅是棲息於沿岸地區,並以沖上岸的海藻為食,但經過400百萬年的演化牠們最終成為完全水生的哺乳動物,以海床上的海草為食,類似於現存的海牛[18]。

根據形態學上的比較,過去認為二趾樹懶是由已滅絕的加勒比地懶演化支分支出來的[19],雖然從超過33種的地懶的骨骼架構中取得資料,但不同種地懶之間的關係仍尚未釐清[20]。

2019年,藉由分析膠原蛋白分子序列[10]及粒線體DNA[21]則更支持了樹懶雙起源的假說,更同時推翻了之前仰賴形態學建立的地懶種系發生樹。這項研究指出二趾樹懶與磨齒獸為近親,而三趾樹懶則屬於大地懶總科,與巨爪地懶、大地懶及懶獸為近親。這代表原本的巨爪地懶科實屬於多系群,現已將二趾樹懶科與加勒比地懶移出巨爪地懶科並成為獨立的科,且加勒比地懶被認為屬於地懶種系發生樹的基群[10][21]。

種系發生學

[编辑]以下演化樹是根據2019年的研究。

| 樹懶亞目 |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

滅絕

[编辑]棲息於南美洲太平洋沿岸的海懶獸於上新世晚期絕種,在巴拿馬地峽的形成後改變了海流方向,因而造成南美洲沿太平洋岸水溫的下降,並使著海懶獸賴以為生的海草大量滅絕。同時海懶獸的低新陳代謝速率使得牠們在低溫的海洋中較難以維持體溫[22]。

南美洲與北美洲的地懶大約於11,000年前現代人類出現時絕種,許多更新世巨型動物群也約於此時絕種。在南美洲與北美洲都曾經有發現地懶被人類殺害、烹煮、食用的相關證據[2]。末次冰河時期結束時所帶來的氣候變遷也可能是地懶滅絕的原因。

棲息於加勒比地區的地懶直到5,000年前人類到來安地列斯群島後才絕種,遠晚於棲息於南北美大陸上的地懶[23]。

生物學

[编辑]

外型

[编辑]樹懶體長約 60至80 cm(24至31英寸),體重約 3.6至7.7公斤(7.9至17.0磅),二趾樹懶的體型較大[24]。樹懶具有長手臂以及外耳不明顯的頭。三趾樹懶有一條長約 5至6 cm(2.0至2.4英寸) 的尾巴。幾乎所有的哺乳動物均有7節頸椎,二趾樹懶只有6節,而三趾樹懶則有9節[25],讓牠們得以270度轉動牠們的頭部[26]。

生理學

[编辑]樹懶具有有色視覺,但視力很差。樹懶的聽力也很差,主要依靠嗅覺與觸覺來尋找食物[27]。

樹懶擁有非常慢的代謝(低於同體型哺乳動物的 50%)及非常低的體溫,活動時體溫僅有30至34 °C(86至93 °F),休息時則更低。樹懶為異溫動物,牠們的體溫會隨著周遭環境溫度而變化,範圍大約在 25至35 °C(77至95 °F),但最低時可能只有 20 °C(68 °F)[27]。

樹懶毛髮的生長方向與其他哺乳動物相反,哺乳動物的毛髮生長一般由脊椎向四肢延伸,但由於樹懶多半倒吊於樹上,四肢位置多半高於軀幹,相反的毛髮生長方向讓這些毛髮得以維持順向並起到保護樹懶的作用。樹懶的毛髮上同時還長有共生性的藻類,能夠提供牠們偽裝[28],減少被美洲豹、豹貓[29]與角鵰發現的機會[30]。樹懶毛髮上也由於長有藻類,形成了獨特的小型生態系,棲息著許多種的片利共生與寄生性節肢動物[31]。寄生性的節肢動物包括會吸血的蚊、白蛉、錐蝽、蝨、蜱與蟎;而行片利共生的節肢動物則包括高度特化的甲蟲、蟎與蛾[32],然而這些節肢動物的糞便也能滋養藻類,使得樹懶能夠從中得利[33]。目前有觀察到身上帶有大量節肢動物的物種包括:白喉三趾樹懶、褐喉三趾樹懶與二趾樹懶[32]。

活動能力

[编辑]樹懶的四肢演化成適合吊掛以及抓握,而非支撐自身體重。肌肉只佔了總體重的25-30%,而其他哺乳動物的肌肉則通常為總體重的40-45%.[34]。四肢上的長爪也能幫助樹懶輕鬆倒掛於樹枝上[35]並在地表時讓樹懶得以爬行,畢竟牠們並沒有行走的能力。另外,三趾樹懶的前肢長度比後肢長50%[27]。

樹懶的移動速度十分緩慢,在樹上時平均速度約為每分鐘4米(13英尺),但遭遇掠食者時也能以每分鐘4.5米(15英尺)的速度移動;若是在地面,則樹懶爬行的速度每分鐘可達3米(9.8英尺)。牠們有時會坐在樹枝上,但多半仍以倒吊為主,即使是進食、睡覺或是生產,甚至死後屍體也會繼續掛在樹枝上。然而,樹懶在游泳時,速度可達每分鐘13.5米(44英尺)[36],藉由划動前肢,樹懶得以橫跨河流或島嶼[37]。樹懶能使牠們很慢的新陳代謝進一步下降,將心跳速率減少至平常的1/3,這讓牠們得以於水中憋氣40分鐘[38]。

野生的褐喉三趾樹懶一天平均睡眠時間為9.6小時[39]。二趾樹懶為夜行性[40];三趾樹懶多半為夜行性,但白天有時也會活動,不過90%的時間都會待在原地[27]。

食性

[编辑]樹懶寶寶透過舔母親唇上殘餘的植物組織來學習那些植物是否適合食用的[41],不過所有樹懶都會以傘樹屬的葉片為食。

二趾樹懶具有較多樣化的食性:包括昆蟲、腐肉、水果、葉子與小型蜥蜴,活動範圍可達 140 公頃。而三趾樹懶只以葉片為食,擁有哺乳動物中最慢的消化速度,終其一生可能都在同一棵樹上度過。樹葉難以消化且營養價值低,所以樹懶須透過巨大的胃與其內共生的細菌來慢慢消化這些樹葉。一隻飽食的樹懶三分之二的體重來自於其胃囊中的內容物,而這些內容物需要至少一個月才能夠消化完全。

樹懶一週一次會爬下樹至地面進行排泄與排遺,在排出後更會將排泄物掩埋,在地面時樹懶十分容易遭到掠食者的捕食。三趾樹懶會在固定的地點排便,而這項行為也能幫助維持樹懶毛上的獨特生態系[42],而埋在樹旁的糞便,則能成為樹木的肥料[43]。最近研究顯示,樹懶蛾會將卵產在樹懶的糞便中,而幼蟲會以這些糞便為食,成年後這些蛾會在樹懶下幾次到地面排便時爬上樹懶的毛中棲息[4]。

繁殖

[编辑]褐喉與白喉三趾樹懶具有特定的繁殖季節,鬃毛三趾樹懶全年皆可繁殖,而侏三趾樹懶的繁殖則仍屬未知。三趾樹懶的妊娠期為六個月,二趾樹懶則為十二個月,一胎只會生下一隻幼崽,幼崽會與母親共同生活約五個月。在有些案例中,當幼崽墜落至地面時,母親會因為不願意爬下安全的樹而選擇遺棄幼崽,進而導致幼崽的喪生[44]。雌樹懶多半一年繁殖一次,但有時會因為行動遲緩找不到雄樹懶而失去繁殖的機會[45]。樹懶並沒有明顯的兩性異形,有時動物園會收到被標示錯誤性別的個體[46][47]。

由於缺乏長時的自然環境調查數據,野生二趾樹懶的平均壽命目前仍然未知[48];人工飼養的個體平均則約為16年,但有其中一隻飼養於史密森尼學會美國國家動物園的二趾樹懶卻有活了49年的紀錄[49]。

天敵

[编辑]樹懶主要天敵之一是角鵰[50],可以無聲無息直接將樹懶抓起。另外美洲豹與豹貓[51]也會獵捕樹懶。

棲息與分布地區

[编辑]

樹懶雖然只分布於中南美洲的熱帶雨林之中,牠們卻是當地十分繁盛的物種。在巴拿馬的巴羅科羅拉多島上,樹懶估計佔了當地樹棲哺乳動物生物質量的70%[52]。六個現存物種之中,有四種為無危物種;棲息於巴西日益縮減的大西洋沿岸森林的鬃毛三趾樹懶,屬於易危物種[53],而棲息於離島上的侏三趾樹懶則為極危物種。樹懶的低新陳代謝導致牠們只能生存於熱帶地區,且牠們必須透過曝曬於陽光下來提高體溫,類似於變溫動物的體溫調節系統[54]。

與人類之互動

[编辑]

在哥斯大黎加,記錄到最主要樹懶的死因為被電線電死以及遭到盜獵。然而牠們的爪子大幅增加了盜獵的難度,因為即使遭到射殺,死掉的樹懶依然會因為牠們的長爪而繼續倒掛於樹上,不會掉落至地面。

人類會非法捕捉樹懶作為寵物販賣,但其實樹懶特殊的生活習性導致牠們並不適合一般民眾飼養[55]。

蘇利南綠色遺產基金會(Green Heritage Fund Suriname)的創始人莫莉卡·普兒(Monique Pool)至今已拯救並釋放了超過600隻的樹懶、食蟻獸、犰狳以及豪豬[56]。

哥斯大黎加樹懶保育研究協會主要的職務在於照顧、使樹懶恢復健康並將牠們釋放回野外[57]。同樣位於哥斯大黎加的哥斯大黎加樹懶收容所主要也以照顧樹懶為主,並已成功釋放了約130隻個體回到野外[58];然而,2016年五月的一篇報導中之前於該收容所工作的兩名獸醫指出,該收容所並沒有給予樹懶真正妥善的照護[59]。

外部連結

[编辑]為什麼樹懶要大費周章爬下樹排便? (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆),來自PanSci 泛科學。

参考文献

[编辑]- ^ 國家教育研究院. sloth - 樹懶;樹懶.:國家教育研究院雙語詞彙、學術名詞暨辭書資訊網, 2017-1-26

- ^ 2.0 2.1 2.2 The Land and Wildlife of South America. Time Inc. 1964: 15, 54 [1 December 2017].

- ^ Overview. The Sloth Conservation Foundation. [29 November 2017]. (原始内容存档于2017-12-01).

- ^ 4.0 4.1 Bennington-Castro, Joseph. The Strange Symbiosis Between Sloths and Moths. Gizmodo. [1 December 2017]. (原始内容存档于2017-12-01).

- ^ Megatherium Wildfacts. BBC. [22 July 2012]. (原始内容存档于February 1, 2014).

- ^ Haines, T.; Chambers, P. The Complete Guide to Prehistoric Life. Italy: Firefly Books Ltd. 2007: 192–193. ISBN 1-55407-181-X.

- ^ O'Leary, Maureen A.; Bloch, Jonathan I.; Flynn, John J.; Gaudin, Timothy J.; Giallombardo, Andres; Giannini, Norberto P.; Goldberg, Suzann L.; Kraatz, Brian P.; Luo, Zhe-Xi. The Placental Mammal Ancestor and the Post–K-Pg Radiation of Placentals. Science. 2013-02-08, 339 (6120): 662–667. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 23393258. doi:10.1126/science.1229237 (英语).

- ^ Svartman, Marta; Stone, Gary; Stanyon, Roscoe. The Ancestral Eutherian Karyotype Is Present in Xenarthra. PLOS Genetics. 2006-07-21, 2 (7): e109. ISSN 1553-7404. PMC 1513266

. PMID 16848642. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.0020109.

. PMID 16848642. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.0020109.

- ^ Delsuc, Frédéric; Catzeflis, François M.; Stanhope, Michael J.; Douzery, Emmanuel J. P. The evolution of armadillos, anteaters and sloths depicted by nuclear and mitochondrial phylogenies: implications for the status of the enigmatic fossil Eurotamandua. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London B: Biological Sciences. 2001-08-07, 268 (1476): 1605–1615. ISSN 0962-8452. PMC 1088784

. PMID 11487408. doi:10.1098/rspb.2001.1702 (英语).

. PMID 11487408. doi:10.1098/rspb.2001.1702 (英语).

- ^ 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 10.4 10.5 Presslee, S.; Slater, G. J.; Pujos, F.; Forasiepi, A. M.; Fischer, R.; Molloy, K.; Mackie, M.; Olsen, J. V.; Kramarz, A.; Taglioretti, M.; Scaglia, F.; Lezcano, M.; Lanata, J. L.; Southon, J.; Feranec, R.; Bloch, J.; Hajduk, A.; Martin, F. M.; Gismondi, R. S.; Reguero, M.; de Muizon, C.; Greenwood, A.; Chait, B. T.; Penkman, K.; Collins, M.; MacPhee, R.D.E. Palaeoproteomics resolves sloth relationships. Nature Ecology & Evolution. 2019, 3 (7): 1121–1130. PMID 31171860. doi:10.1038/s41559-019-0909-z.

- ^ Gardner, Alfred. Wilson, D. E., and Reeder, D. M. (eds) , 编. Mammal Species of the World 3rd edition. Johns Hopkins University Press. November 16, 2005: 100–101. ISBN 0-801-88221-4.

- ^ Gardner, Alfred L. Suborder Folivora. Gardner, Alfred L. (编). Mammals of South America, Volume 1: Marsupials, Xenarthrans, Shrews, and Bats. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. 2007: 157–168 (p. 161) [2019-01-02]. ISBN 978-0-226-28240-4. (原始内容存档于2018-11-27).

- ^ Plese, T.; Chiarello, A. Choloepus hoffmanni. IUCN Red List of Threatened Species (IUCN). 2014, 2014: e.T4778A47439751 [27 August 2016]. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2014-1.RLTS.T4778A47439751.en.[永久失效連結]

- ^ Hayssen, V. Choloepus hoffmanni (Pilosa: Megalonychidae). Mammalian Species. 2011, 43 (1): 37–55. doi:10.1644/873.1.

- ^ Gaudin, Timothy J. Phylogenetic relationships among sloths (Mammalia, Xenarthra, Tardigrada): the craniodental evidence. Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society. 2004-02-01, 140 (2): 255–305 [2018-10-26]. ISSN 0024-4082. doi:10.1111/j.1096-3642.2003.00100.x. (原始内容存档于2017-05-18).

- ^ Raj Pant, Sara; Goswami, Anjali; Finarelli, John A. Complex body size trends in the evolution of sloths (Xenarthra: Pilosa). BMC Evolutionary Biology. 2014, 14: 184. PMC 4243956

. PMID 25319928. doi:10.1186/s12862-014-0184-1.

. PMID 25319928. doi:10.1186/s12862-014-0184-1.

- ^ Muizon, C. de; McDonald, H. G.; Salas, R.; Urbina, M. The evolution of feeding adaptations of the aquatic sloth Thalassocnus. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. June 2004, 24 (2): 398–410. JSTOR 4524727. doi:10.1671/2429b.

- ^ Amson, E.; Muizon, C. de; Laurin, M.; Argot, C.; Buffrénil, V. de. Gradual adaptation of bone structure to aquatic lifestyle in extinct sloths from Peru. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 2014, 281 (1782): 20140192. PMC 3973278

. PMID 24621950. doi:10.1098/rspb.2014.0192.

. PMID 24621950. doi:10.1098/rspb.2014.0192.

- ^ White, J.L.; MacPhee, R.D.E. The sloths of the West Indies: a systematic and phylogenetic review. Woods, C.A.; Sergile, F.E. (编). Biogeography of the West Indies: Patterns and Perspectives. CRC Press. 2001: 201–235 [2020-03-26]. ISBN 978-0-8493-2001-9. (原始内容存档于2020-09-19).

- ^ Gaudin, Timothy. Phylogenetic Relationships among Sloths (Mammalia, Xenarthra, Tardigrada): The Craniodental Evidence.. Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society. 2004, 140 (2): 255–305. doi:10.1111/j.1096-3642.2003.00100.x.

- ^ 21.0 21.1 Delsuc, F.; Kuch, M.; Gibb, G. C.; Karpinski, E.; Hackenberger, D.; Szpak, P.; Martínez, J. G.; Mead, J. I.; McDonald, H. G.; MacPhee, R.D.E.; Billet, G.; Hautier, L.; Poinar, H. N. Ancient Mitogenomes Reveal the Evolutionary History and Biogeography of Sloths. Current Biology. 2019, 29 (12): 2031–2042.e6. PMID 31178321. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2019.05.043.

- ^ Amson, E.; Argot, C.; McDonald, H. G.; de Muizon, C. Osteology and functional morphology of the axial postcranium of the marine sloth Thalassocnus (Mammalia, Tardigrada) with paleobiological implications. Journal of Mammalian Evolution. 2015, 22 (4): 473–518. doi:10.1007/s10914-014-9280-7.

- ^ Steadman, D. W.; Martin, P. S.; MacPhee, R. D. E.; Jull, A. J. T.; McDonald, H. G.; Woods, C. A.; Iturralde-Vinent, M.; Hodgins, G. W. L. Asynchronous extinction of late Quaternary sloths on continents and islands. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2005-08-16, 102 (33): 11763–11768. PMC 1187974

. PMID 16085711. doi:10.1073/pnas.0502777102.

. PMID 16085711. doi:10.1073/pnas.0502777102.

- ^ Sloth. National Geographic. [1 December 2017]. (原始内容存档于2019-04-11).

- ^ Narita, Yuichi; Kuratani, Shigeru. Evolution of the vertebral formulae in mammals: A perspective on developmental constraints. Journal of Experimental Zoology Part B: Molecular and Developmental Evolution. 2005-03-15, 304B (2): 91–106 [2018-10-25]. ISSN 1552-5015. doi:10.1002/jez.b.21029. (原始内容存档于2017-12-01) (英语).

- ^ Three-Toed Sloths. National Geographic. [1 December 2017]. (原始内容存档于2021-01-24).

- ^ 27.0 27.1 27.2 27.3 Sloth. Encyclopedia Brittanica. [1 December 2017]. (原始内容存档于2017-05-19).

- ^ Suutari, Milla; Majaneva, Markus; Fewer, David P.; Voirin, Bryson; Aiello, Annette; Friedl, Thomas; Chiarello, Adriano G.; Blomster, Jaanika. Molecular evidence for a diverse green algal community growing in the hair of sloths and a specific association with Trichophilus welckeri(Chlorophyta, Ulvophyceae). BMC Evolutionary Biology. 2010-01-01, 10: 86. ISSN 1471-2148. PMC 2858742

. PMID 20353556. doi:10.1186/1471-2148-10-86.

. PMID 20353556. doi:10.1186/1471-2148-10-86.

- ^ Moreno, Ricardo S.; Kays, Roland W.; Samudio, Rafael. Competitive Release in Diets of Ocelot (Leopardus pardalis) and Puma (Puma concolor) after Jaguar (Panthera onca) Decline. Journal of Mammalogy. 2006-08-24, 87 (4): 808–816. ISSN 0022-2372. doi:10.1644/05-MAMM-A-360R2.1.

- ^ Aguiar-Silva, F. Helena; Sanaiotti, Tânia M.; Luz, Benjamim B. Food Habits of the Harpy Eagle, a Top Predator from the Amazonian Rainforest Canopy. Journal of Raptor Research. 2014-03-01, 48 (1): 24–35. ISSN 0892-1016. doi:10.3356/JRR-13-00017.1.

- ^ Gilmore, D. P.; Da Costa, C. P.; Duarte, D. P. F. Sloth biology: an update on their physiological ecology, behavior and role as vectors of arthropods and arboviruses. Brazilian Journal of Medical and Biological Research. 2001-01-01, 34 (1): 9–25. ISSN 0100-879X. PMID 11151024. doi:10.1590/S0100-879X2001000100002.

- ^ 32.0 32.1 Gilmore, D. P.; Da Costa, C. P.; Duarte, D. P. F. Sloth biology: an update on their physiological ecology, behavior and role as vectors of arthropods and arboviruses (PDF). Brazilian Journal of Medical and Biological Research. 2001, 34 (1): 9–25 [2020-03-23]. ISSN 1678-4510. PMID 11151024. doi:10.1590/S0100-879X2001000100002. (原始内容存档 (PDF)于2020-11-06).

- ^ Ed Yong. Can Moths Explain Why Sloths Poo On the Ground?. Phenomena. 2014-01-21 [2020-03-23]. (原始内容存档于2018-05-29).

- ^ What Does It Mean to Be a Sloth?. natureinstitute.org. [2017-06-29]. (原始内容存档于2019-06-15).

- ^ Mendel, Frank C. Use of Hands and Feet of Three-Toed Sloths (Bradypus variegatus) during Climbing and Terrestrial Locomotion. Journal of Mammalogy. 1985-01-01, 66 (2): 359–366. JSTOR 1381249. doi:10.2307/1381249.

- ^ Goffart, M. Function and Form in the sloth. International Series of Monographs in Pure and Applied Biology. 1971, 34: 94–95.

- ^ BBC, Swimming sloth - Planet Earth II: Islands Preview - BBC One, 2016-11-04 [2017-04-17], (原始内容存档于2021-02-21)

- ^ Britton, S. W. Form and Function in the Sloth. The Quarterly Review of Biology. 1941-01-01, 16 (1): 13–34. JSTOR 2808832. doi:10.1086/394620.

- ^ Briggs, Helen. Article "Sloth's Lazy Image 'A Myth'". BBC News. 2008-05-13 [2010-05-21]. (原始内容存档于2021-01-01).

- ^ Eisenberg, John F.; Redford, Kent H. Mammals of the Neotropics, Volume 3: The Central Neotropics: Ecuador, Peru, Bolivia, Brazil. University of Chicago Press. May 15, 2000: 624 (see pp. 94–95, 97) [2020-03-24]. ISBN 978-0-226-19542-1. OCLC 493329394. (原始内容存档于2020-09-19).

- ^ Venema, Vibeke. The woman who got 'slothified'. BBC News. 2014-04-04 [2017-12-01]. (原始内容存档于2021-03-06) (英国英语).

- ^ Title:A syndrome of mutualism reinforces the lifestyle of a sloth Authors:Jonathan N. Pauli, Jorge E. Mendoza, Shawn A. Steffan, Cayelan C.Carey, Paul J. Weimer and M. Zachariah Peery Journal:Proceedings of the Royal Society B

- ^ Montgomery, Sy. Community Ecology of the Sloth. Cecropia: Supplemental Information. Encyclopædia Britannica. [2009-09-06]. (原始内容存档于2009-05-24).

- ^ Soares, C. A.; Carneiro, R. S. Social behavior between mothers × young of sloths Bradypus variegatus SCHINZ, 1825 (Xenarthra: Bradypodidae). Brazilian Journal of Biology. 2002-05-01, 62 (2): 249–252. ISSN 1519-6984. PMID 12489397. doi:10.1590/S1519-69842002000200008.

- ^ Pauli, Jonathan N.; Peery, M. Zachariah. Unexpected Strong Polygyny in the Brown-Throated Three-Toed Sloth. PLOS One. 2012-12-19, 7 (12): e51389. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 3526605

. PMID 23284687. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0051389.

. PMID 23284687. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0051389.

- ^ Manly secret of non-mating sloth at London Zoo. BBC News (BBC). 19 August 2010 [30 April 2015]. (原始内容存档于2020-09-19).

- ^ Same-sex sloths dash Drusillas breeding plan. BBC News (BBC). 5 December 2013 [30 April 2015]. (原始内容存档于2020-12-05).

- ^ About the Sloth. Sloth Conservation Foundation. [31 October 2019]. (原始内容存档于2021-01-16).

- ^ Southern two-toed sloth. Smithsonian's National Zoo. 2016-04-25 [2019-10-30]. (原始内容存档于2019-07-17) (英语).

- ^ Aguiar-Silva, F. Helena; Sanaiotti, Tânia M.; Luz, Benjamim B. Food Habits of the Harpy Eagle, a Top Predator from the Amazonian Rainforest Canopy. Journal of Raptor Research. 2014-03-01, 48 (1): 24–35 [2018-10-26]. ISSN 0892-1016. doi:10.3356/JRR-13-00017.1. (原始内容存档于2024-05-23).

- ^ Moreno, Ricardo S.; Kays, Roland W.; Samudio, Rafael. Competitive Release in Diets of Ocelot (Leopardus pardalis) and Puma (Puma concolor) after Jaguar (Panthera onca) Decline. Journal of Mammalogy. 2006-08-24, 87 (4): 808–816 [2018-10-26]. ISSN 0022-2372. doi:10.1644/05-MAMM-A-360R2.1. (原始内容存档于2017-05-18).

- ^ Eisenberg, John F.; Redford, Kent H. Mammals of the Neotropics, Volume 3: The Central Neotropics: Ecuador, Peru, Bolivia, Brazil. University of Chicago Press. May 15, 2000: 624 (see p. 96) [2020-01-07]. ISBN 978-0-226-19542-1. OCLC 493329394. (原始内容存档于2020-09-19).

- ^ Chiarello, A. & Moraes-Barros, N. Bradypus torquatus. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2014, 2014: e.T3036A47436575. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2014-1.RLTS.T3036A47436575.en

.

.

- ^ Dowling, Stephen. Why do sloths move so slowly?. BBC Future (BBC News). 29 August 2019 [2 September 2019]. (原始内容存档于2019-09-12).

- ^ News, A. B. C. Sloths: Hottest-Selling Animal in Colombia's Illegal Pet Trade. ABC News. 2013-05-29 [2017-12-02]. (原始内容存档于2021-02-10).

- ^ When sloths are in trouble, she's the one to call. CNN. [2017-12-01]. (原始内容存档于2021-01-21).

- ^ The Sloth Institute website. [2021-12-31]. (原始内容存档于2021-03-31).

- ^ Sevcenko, Melanie. Sloth sanctuary nurtures animals back to health. Deutsche Welle. 2013-04-17 [2013-04-18]. (原始内容存档于2015-05-13).

- ^ Schelling, Ameena. Famous Sloth Sanctuary Is A Nightmare For Animals, Ex-Workers Say. The Dodo. 2016-05-19 [2016-05-20]. (原始内容存档于2021-01-18).

警告:默认排序键“樹懒”覆盖了之前的默认排序键“Folivora”。